- Physics & Mathematics

What was the loudest sound ever recorded?

Features

By

Clarissa Brincat

published

7 December 2025

What was the loudest sound ever recorded?

Features

By

Clarissa Brincat

published

7 December 2025

Determining the "loudest recorded sound" depends on how you define sound and on which measurements you choose to include.

0 Comments Join the conversationWhen you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

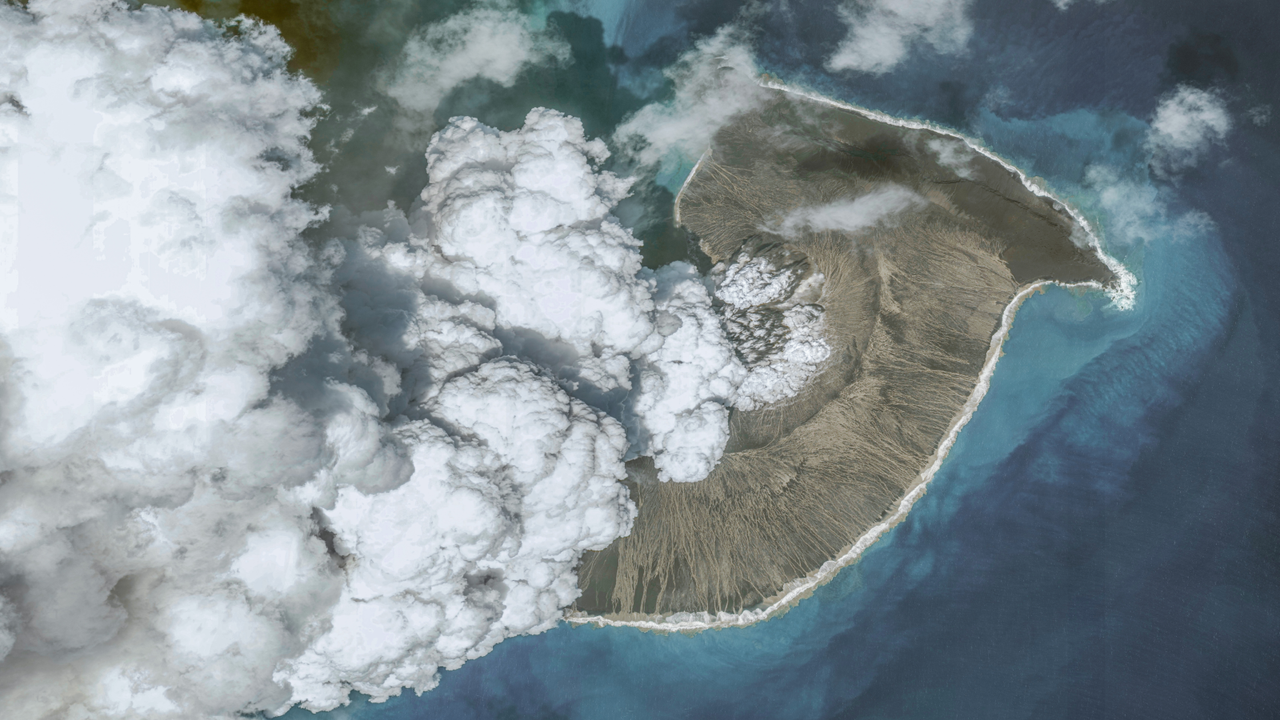

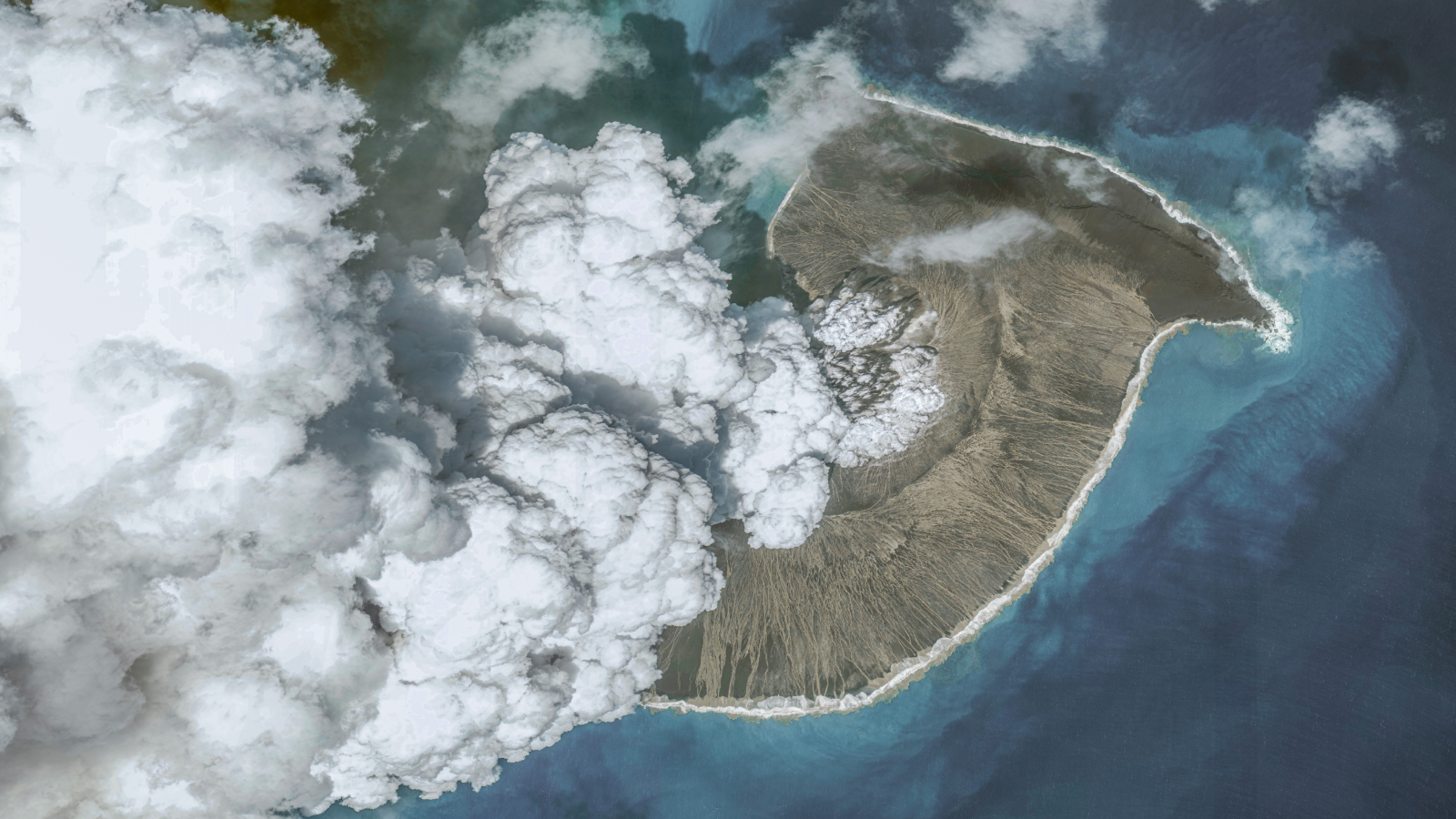

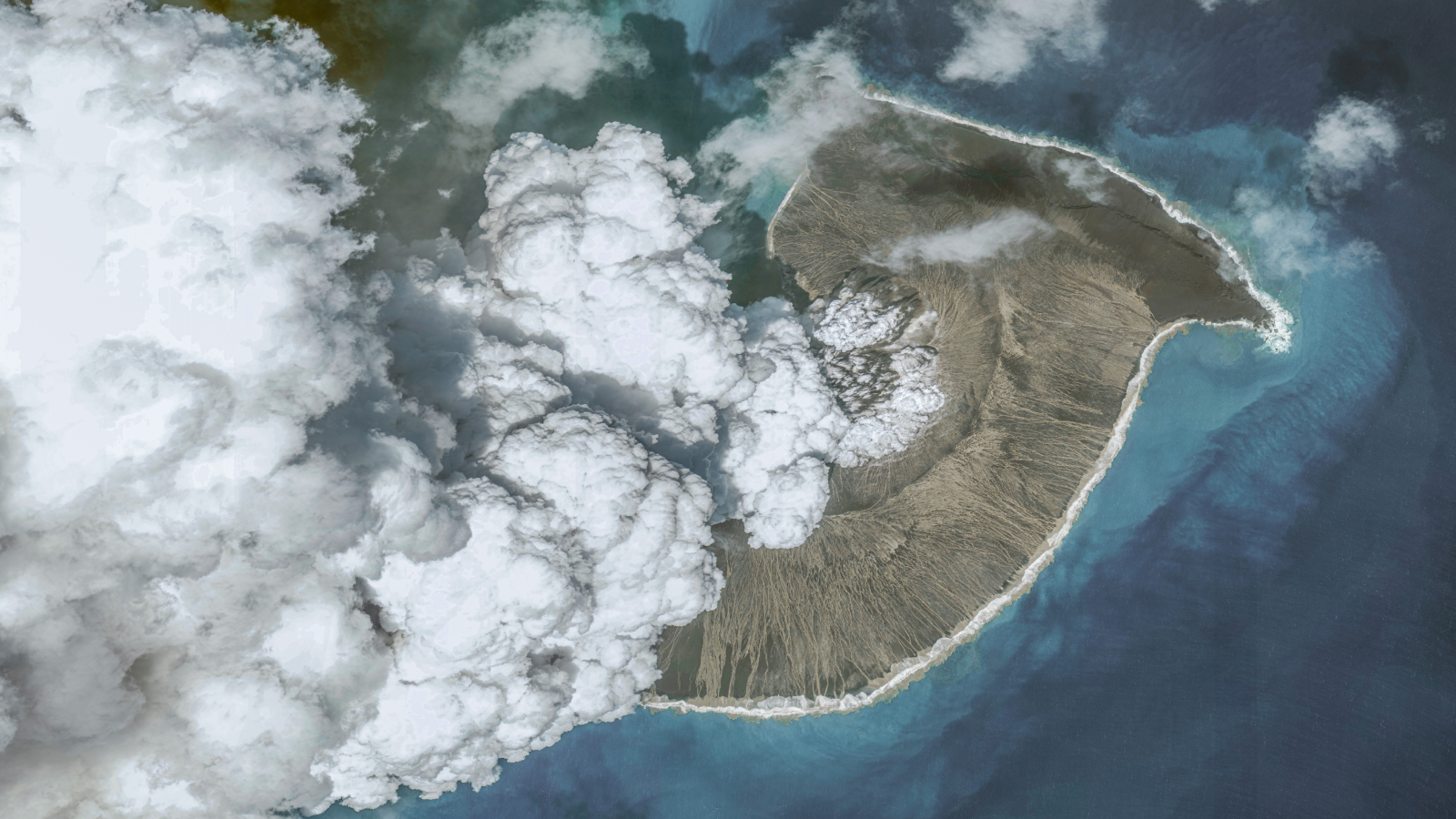

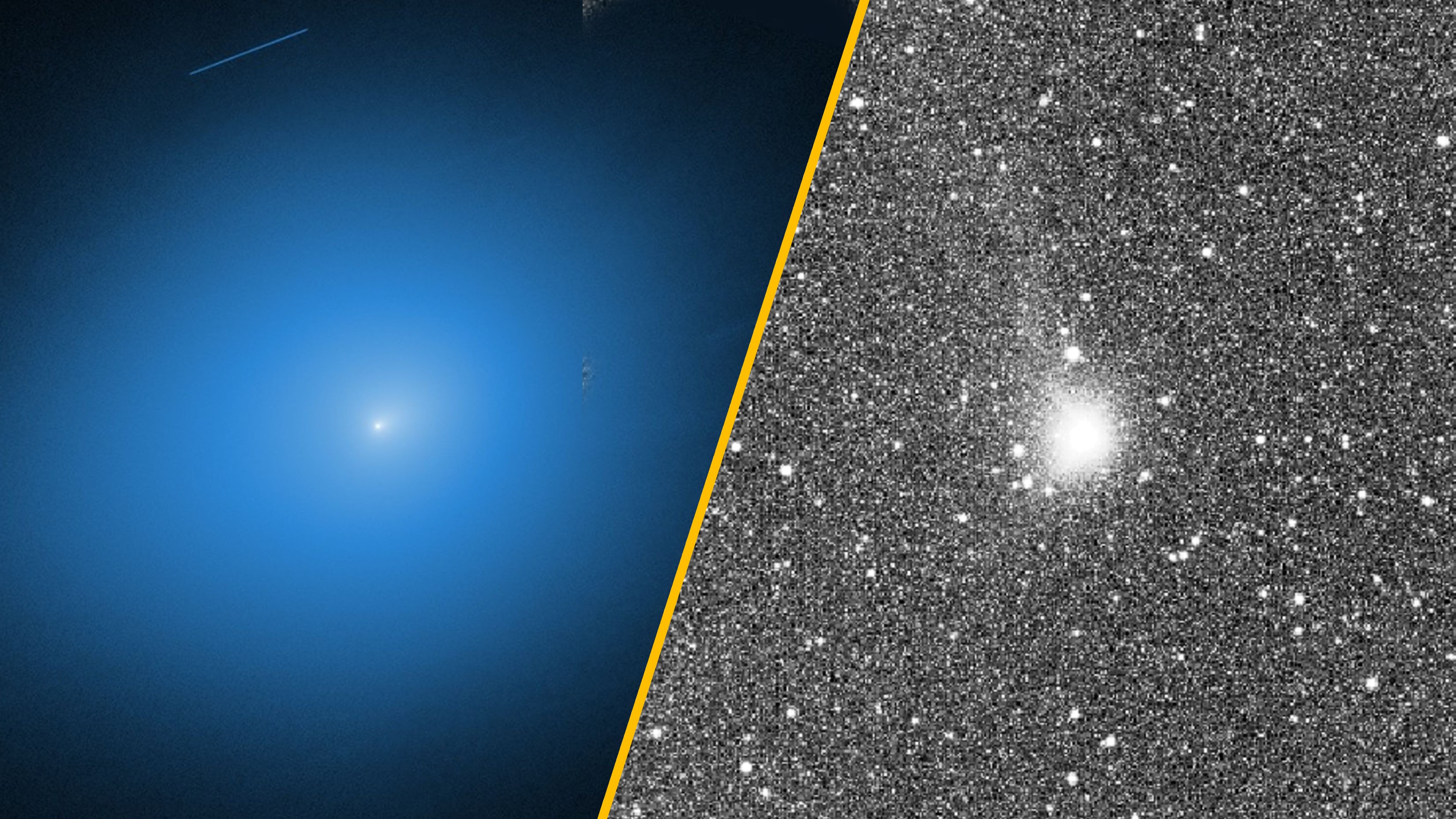

The eruption of the underwater volcano Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai produced one of the loudest recorded sounds in history.

(Image credit: Photo by Maxar via Getty Images)

The eruption of the underwater volcano Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai produced one of the loudest recorded sounds in history.

(Image credit: Photo by Maxar via Getty Images)

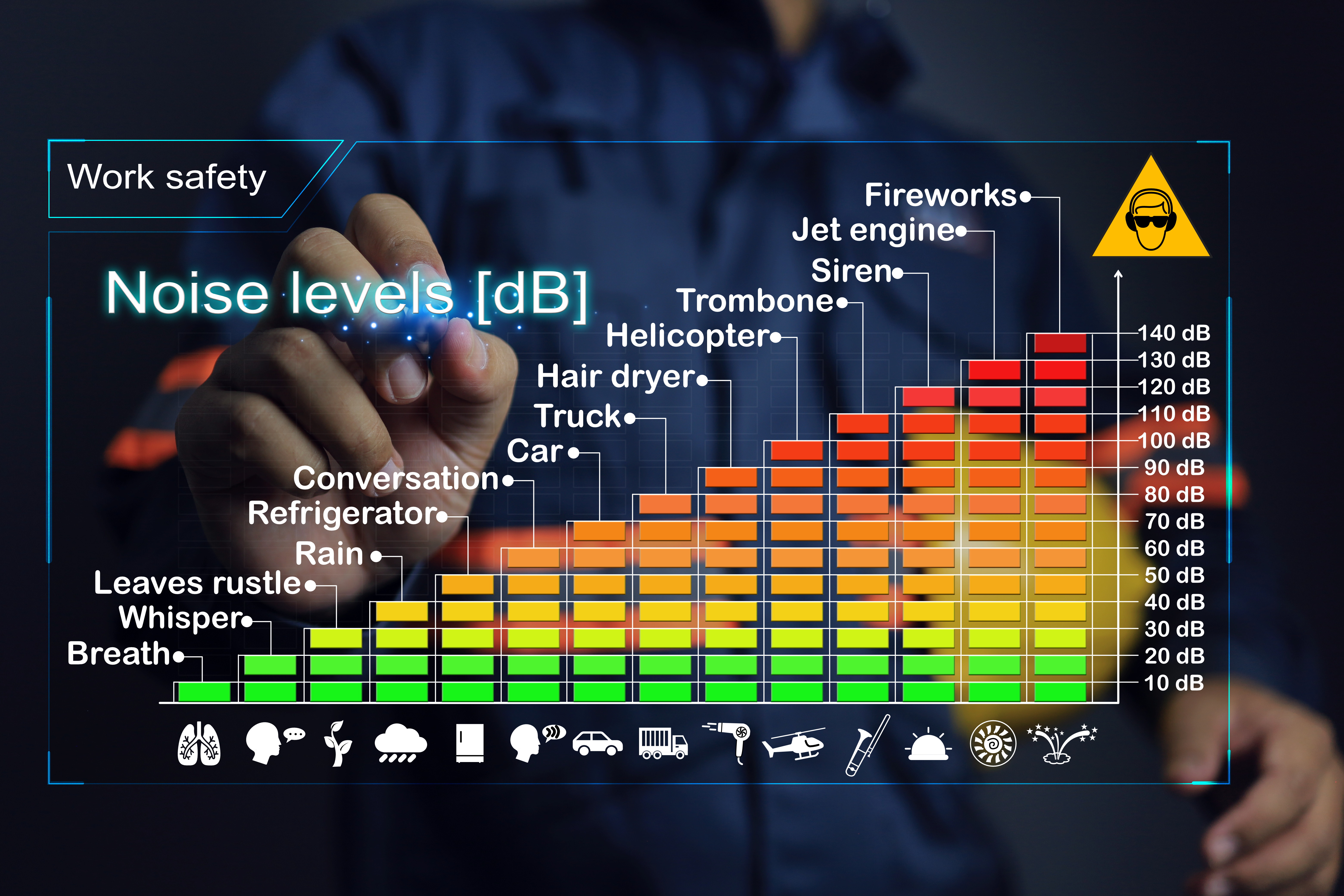

Live concerts, fireworks and roaring stadium crowds can reach dangerously high volumes — loud enough to cause permanent hearing loss. But what was the loudest sound ever recorded on Earth?

The answer depends on what you mean by "sound" and whether you include old historical reports or only trust measurements made with modern scientific instruments.

The 1883 eruption of Krakatau (also spelled Krakatoa), a volcanic island in Indonesia, is often considered the loudest sound in history. People heard the blast more than 1,900 miles (3,000 kilometers) away, and barometers around the world picked up its pressure wave. At 100 miles (160 km) away, the eruption reached an estimated 170 decibels — enough to cause permanent hearing damage. At 40 miles (64 km) away, the boom was strong enough to rupture eardrums, sailors reported.

You may like-

Astronomers detect first 'heartbeat' of a newborn star hidden within a powerful cosmic explosion

Astronomers detect first 'heartbeat' of a newborn star hidden within a powerful cosmic explosion

-

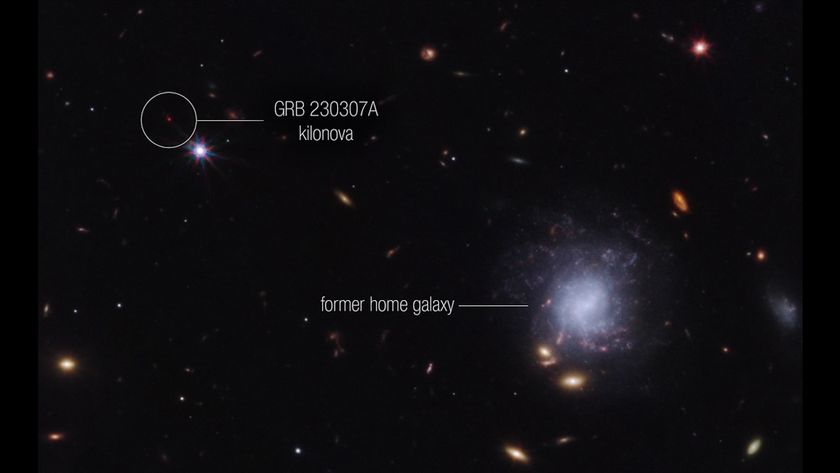

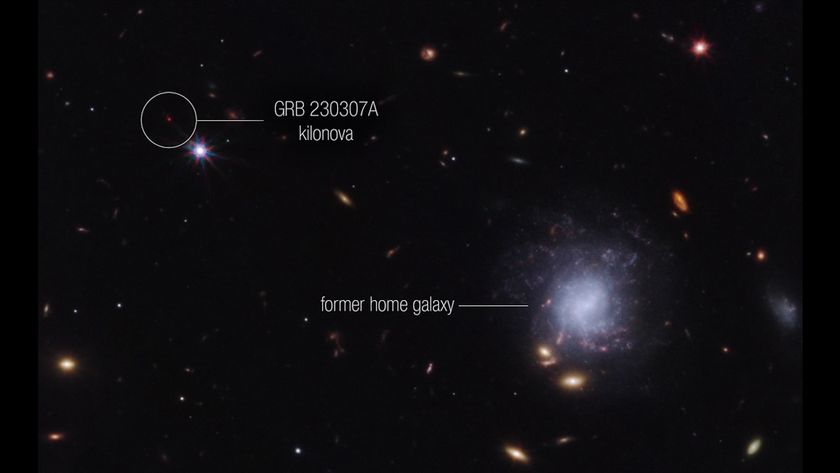

Mysterious cosmic explosion can't be explained, scientists say

Mysterious cosmic explosion can't be explained, scientists say

-

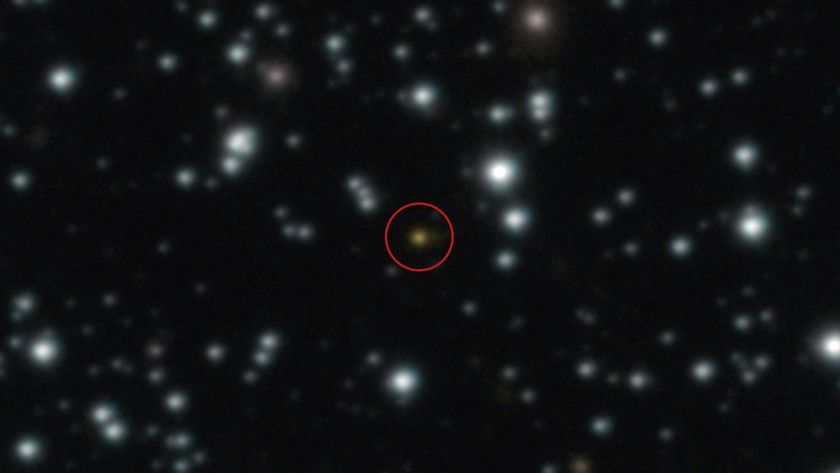

Confirmed! Black hole merger shows Stephen Hawking theory was right

Confirmed! Black hole merger shows Stephen Hawking theory was right

Typically, people can tolerate sounds up to around 140 decibels, beyond which sound becomes painful and unbearable. Hearing damage can occur after listening to 85 decibels for a few hours, 100 decibels for 14 minutes or 110 decibels for two minutes, according to the National Institutes of Health. Meanwhile, a vacuum cleaner is around 75 decibels, a chainsaw is about 110 decibels and a jet engine is approximately 140 decibels.

Sign up for our newsletter

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

Modern estimates suggest that the Krakatau blast reached about 310 decibels. At this level, sound waves no longer behave like normal sound (which causes particles to vibrate and creates areas of compression and rarefaction). Instead, at around 194 decibels, they turn into shock waves — powerful pressure fronts created when something moves faster than the speed of sound. Krakatau's shock wave was so strong that it circled the planet seven times.

But Michael Vorländer, a professor and head of the Institute for Hearing Technology and Acoustics at RWTH Aachen University in Germany and president of the Acoustical Society of America, said we don't really know how loud the Krakatau eruption was at its source because no one was close enough to measure it.

"Assumptions can be made about sound propagation, but these are extremely uncertain," he told Live Science in an email.

Another contender for the loudest sound is the 1908 Tunguska meteor explosion over Siberia that flattened trees across hundreds of square miles and sent pressure waves around the world. The Tunguska explosion was approximately as loud as the Krakatau blast — at circa 300 to 315 decibels — but like the Krakatau eruption, the Tunguska blast was recorded only by instruments that were very far away.

Loudest sound in the modern era

If you limit the question to the modern era — that is, when scientists have had a global network of barometers and infrasound sensors — a much more recent event takes the grand prize.

"I believe the 'loudest' sound recorded is the January 2022 eruption of Hunga, Tonga," David Fee, a research professor at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, told Live Science in an email. "This massive volcanic eruption produced a sound wave that traversed the globe multiple times and was heard by humans thousands of miles away, including in Alaska and Central Europe."

You may like-

Astronomers detect first 'heartbeat' of a newborn star hidden within a powerful cosmic explosion

Astronomers detect first 'heartbeat' of a newborn star hidden within a powerful cosmic explosion

-

Mysterious cosmic explosion can't be explained, scientists say

Mysterious cosmic explosion can't be explained, scientists say

-

Confirmed! Black hole merger shows Stephen Hawking theory was right

Confirmed! Black hole merger shows Stephen Hawking theory was right

Milton Garces, founder and director of the Infrasound Laboratory at the University of Hawaii, agrees. "If you were to reframe the question as, 'What is the loudest sound recorded in the modern digital epoch?', then without a doubt the loudest sound was from Tonga in '22," he told Live Science in an email.

One of the closest scientific stations to the underwater eruption — located in Nukua'lofa, about 42 miles (68 km) away — recorded a pressure jump of about 1,800 pascals. (A 200 megaton chemical explosive blast would create about 567 pascals overpressure at a distance of about 560 miles, or 737 km, Garces explained.) If you were to try to turn that into a normal "decibel" number at 3 feet (1 meter) from the source, you'd get about 256 decibels. But Garces said that would be bad science, because this wasn't a normal sound wave at all. Close to the source, it acted more like fast-moving air being pushed outward by the explosion. The Tonga blast was simply too big to fit into the normal decibel scale.

Human-made sounds

Strangely, the most powerful pressure wave in recent history was mostly inaudible to people because it was beyond the range of human hearing, Fee noted.

Scientists have tried to create huge pressure waves in laboratories. In one experiment, researchers used an X-ray laser to blast a microscopic water jet, which produced a pressure wave estimated at about 270 decibels. (That's even louder than the launch of the Saturn V rocket that carried Apollo astronauts to the moon, which was estimated at about 203 decibels.)

RELATED MYSTERIES—What if the speed of sound were as fast as the speed of light?

—What's the tallest wave ever recorded on Earth?

—What's the longest lightning bolt ever recorded?

However, the laser experiment was done inside a vacuum chamber, so the 270-decibel pressure wave was completely silent. Sound waves need a medium — such as air, water or solid material — to travel.

"Pressures in a vacuum chamber are kinda cheating," Garces said. "That's like pressure in space: a supernova may generate huge radiation pressure, but it would not radiate as what we call sound."

"For the most powerful sound-like wave recorded in the modern era," Garces said, "Tonga 2022 is the champ."

TOPICS Life's Little Mysteries Clarissa BrincatLive Science Contributor

Clarissa BrincatLive Science ContributorClarissa Brincat is a freelance writer specializing in health and medical research. After completing an MSc in chemistry, she realized she would rather write about science than do it. She learned how to edit scientific papers in a stint as a chemistry copyeditor, before moving on to a medical writer role at a healthcare company. Writing for doctors and experts has its rewards, but Clarissa wanted to communicate with a wider audience, which naturally led her to freelance health and science writing. Her work has also appeared in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Logout Read more Astronomers detect first 'heartbeat' of a newborn star hidden within a powerful cosmic explosion

Astronomers detect first 'heartbeat' of a newborn star hidden within a powerful cosmic explosion

Mysterious cosmic explosion can't be explained, scientists say

Mysterious cosmic explosion can't be explained, scientists say

Confirmed! Black hole merger shows Stephen Hawking theory was right

Confirmed! Black hole merger shows Stephen Hawking theory was right

'Unlike any we've ever seen': Record-breaking black hole eruption is brighter than 10 trillion suns

'Unlike any we've ever seen': Record-breaking black hole eruption is brighter than 10 trillion suns

Death Valley's 'world's hottest temperature' record may be due to a human error

Death Valley's 'world's hottest temperature' record may be due to a human error

Science news this week: A human population isolated for 100,000 years, the biggest spinning structure in the universe, and a pit full of skulls

Latest in Physics & Mathematics

Science news this week: A human population isolated for 100,000 years, the biggest spinning structure in the universe, and a pit full of skulls

Latest in Physics & Mathematics

Law of 'maximal randomness' explains how broken objects shatter in the most annoying way possible

Law of 'maximal randomness' explains how broken objects shatter in the most annoying way possible

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

Did a NASA telescope really 'see' dark matter? Strange gamma-rays spark bold claims, but scientists urge caution

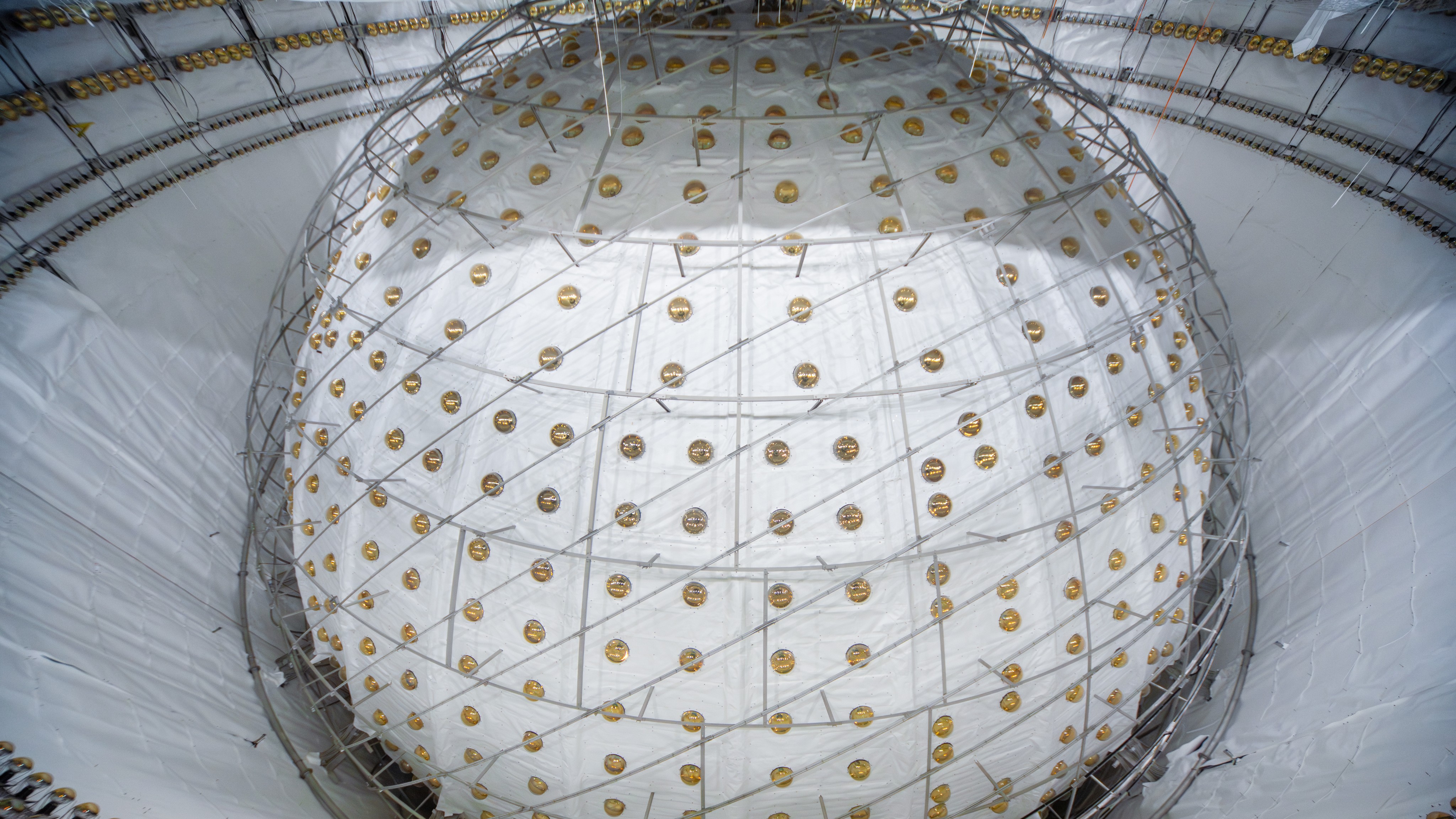

World's largest neutrino detector starts up — with incredible results

World's largest neutrino detector starts up — with incredible results

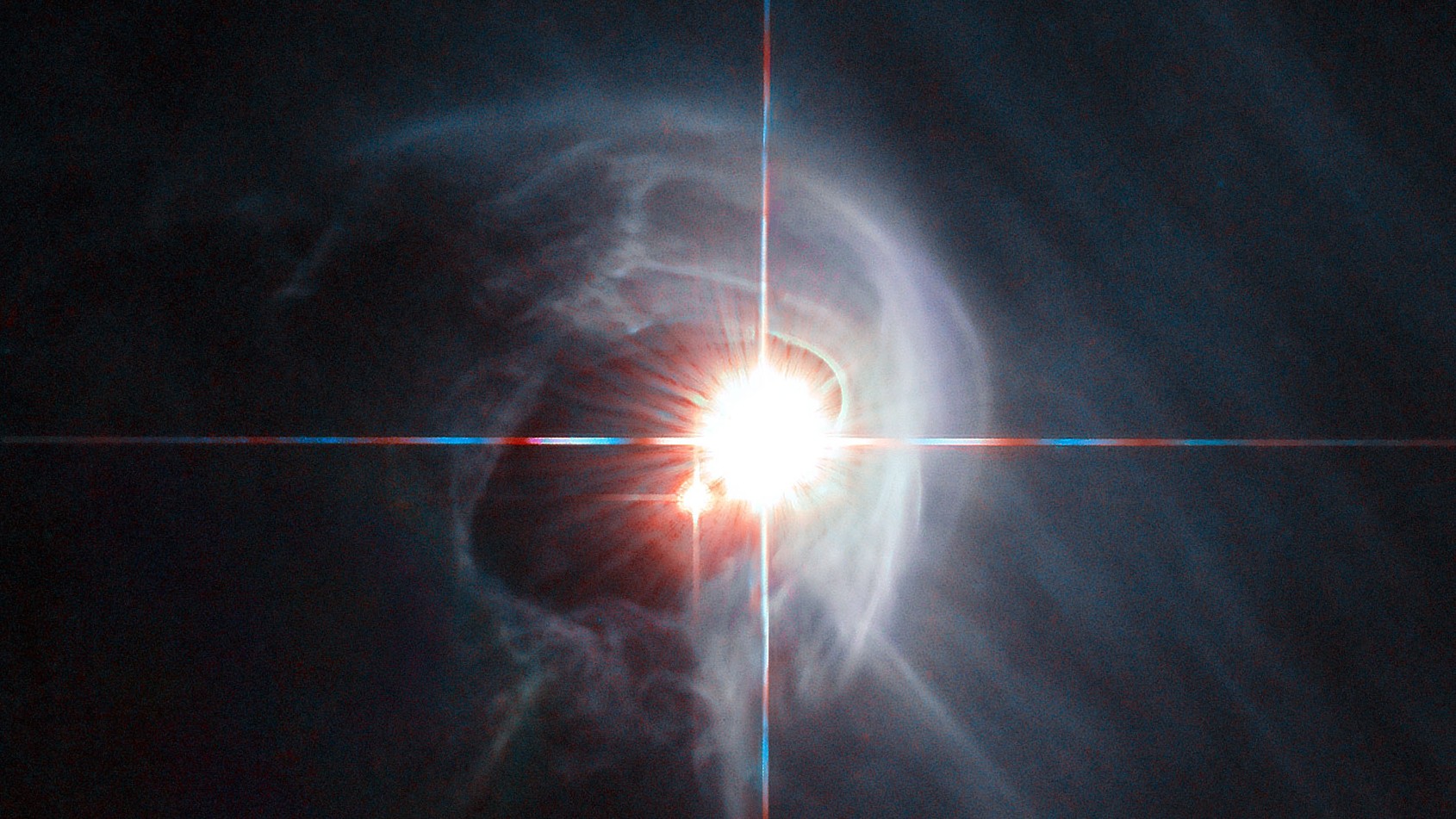

Two stars spiraling toward catastrophe are putting Einstein's gravity to the test

Two stars spiraling toward catastrophe are putting Einstein's gravity to the test

Science history: Russian mathematician quietly publishes paper — and solves one of the most famous unsolved conjectures in mathematics — Nov. 11, 2002

Science history: Russian mathematician quietly publishes paper — and solves one of the most famous unsolved conjectures in mathematics — Nov. 11, 2002

For the first time, physicists peer inside the nucleus of a molecule using electrons as a probe

Latest in Features

For the first time, physicists peer inside the nucleus of a molecule using electrons as a probe

Latest in Features

Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954

Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954

What if Antony and Cleopatra had defeated Octavian?

What if Antony and Cleopatra had defeated Octavian?

What was the loudest sound ever recorded?

What was the loudest sound ever recorded?

A woman got a rare parasitic lung infection after eating raw frogs

A woman got a rare parasitic lung infection after eating raw frogs

Science history: Computer scientist lays out 'Moore's law,' guiding chip design for a half century — Dec. 2, 1964

Science history: Computer scientist lays out 'Moore's law,' guiding chip design for a half century — Dec. 2, 1964

'Intelligence comes at a price, and for many species, the benefits just aren't worth it': A neuroscientist's take on how human intellect evolved

LATEST ARTICLES

'Intelligence comes at a price, and for many species, the benefits just aren't worth it': A neuroscientist's take on how human intellect evolved

LATEST ARTICLES 1New NASA, ESA images show 3I/ATLAS getting active ahead of its close encounter with Earth

1New NASA, ESA images show 3I/ATLAS getting active ahead of its close encounter with Earth- 2Unusual, 1,400-year-old cube-shaped human skull unearthed in Mexico

- 31,800-year-old 'piggy banks' full of Roman-era coins unearthed in French village

- 4What if Antony and Cleopatra had defeated Octavian?

- 5Science history: Female chemist initially barred from research helps helps develop drug for remarkable-but-short-lived recovery in children with leukemia — Dec. 6, 1954